Not the Democrats. Before I tell you who I support, I've answered your questions directly. Your turn to answer a question directly: why do you support Democrats when they support murdering old people? Why do you support Democrats when they support murdering babies before they are born? Why do you support Democrats when they hurt people with lies about the current sickness? Why do you support Democrats when they hurt people by saying riots and looting are "peaceful protests" - which encourages rioting and looting?You don't? Good for you! Who do you support then?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

31 Reasons To Reject The Jab

- Thread starter Jefferson

- Start date

Post a quote of me supporting Democrats when they support murdering old people. Or is that just you putting words in my mouth?Not the Democrats. Before I tell you who I support, I've answered your questions directly. Your turn to answer a question directly: why do you support Democrats when they support murdering old people?

You don't know medical law very well. It is illegal sometimes to ignore the CDC.Why don't the unvaccinated just take hydroxychloroquine and be done with it? No need for a hospital.

There's no law saying you have to go to the hospital.You don't know medical law very well. It is illegal sometimes to ignore the CDC.

There is no law preventing me from calling you stupid either.There's no law saying you have to go to the hospital.

ok doser

lifeguard at the cement pond

You will be REQUIRED to take the un-vaccine shot, or you won't be allowed to travel or buy and sell goods. Or breathe the air.When the truth comes all the way out, you won't be able to get unvaxxed.

ok doser

lifeguard at the cement pond

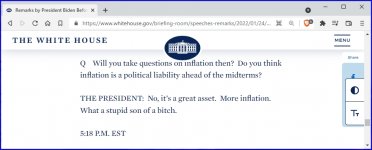

An angry senile puppet who can't control his emotions. The guy with his finger on the nuclear button.

expos4ever

Well-known member

No doubt peer-reviewed by the highly-qualified epidemiologists at the Waffle House.

musterion

Well-known member

An angry senile puppet who can't control his emotions. The guy with his finger on the nuclear button.

Actually the Kenyan's finger but yeah.

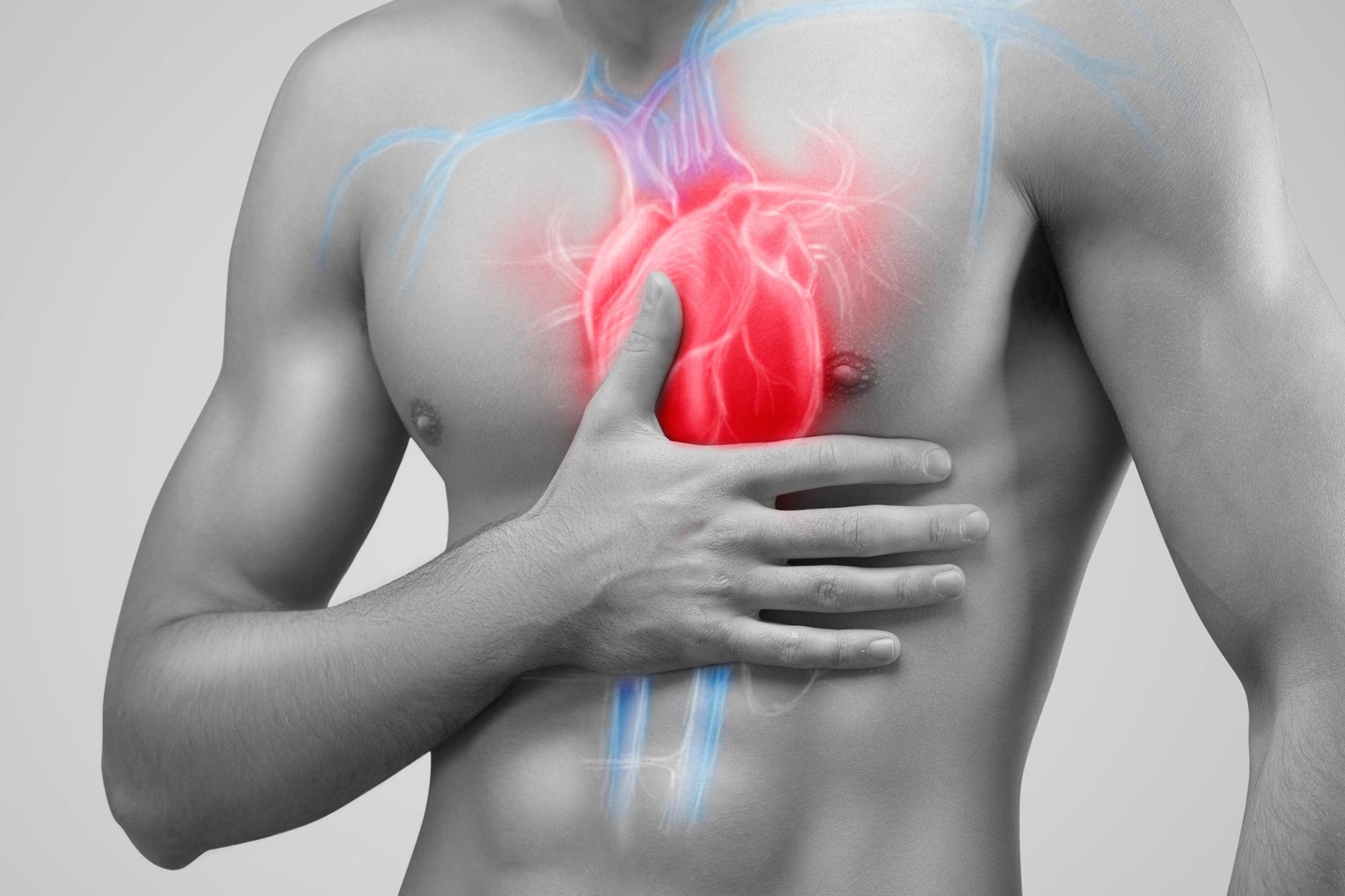

Myocarditis following COVID-19 vaccination is rare and the risk is much smaller than the risks of cardiac injury linked to COVID-19 itself.

Based on a study out of Israel, the risk of post-vaccine myocarditis is 2.13 cases per 100,000 vaccinated, which is within the range usually seen in the general population. This study is consistent with others in the United States and Israel which put the overall incidence of post-vaccine myocarditis between 0.3 and five cases per 100,000 people.

The highest incidence of myocarditis after vaccination with mRNA vaccines has occurred within three to four days after the second vaccination in males who are under age 30. In pediatric data, the median age is 15.8 years, with most patients being male (90.6 percent) and white (66.2 percent) or Hispanic (20.9 percent). Reliable data on booster shots in this age group is not yet available.

Most studies show a clear benefit of COVID-19 mRNA vaccination with respect to myocarditis. Only one study by Martina Patone, from the University of Oxford, and colleagues found more ambiguous results for those under 40 years of age based on myocarditis rates alone. However, if considering the other ill effects of infection with SARS-CoV-2 — both cardiac and not — there was still a strong benefit in immunizing younger people with COVID-19 vaccines other than Moderna, which research suggests has a higher risk for myocarditis than Pfizer’s vaccine.

Considering all of the available research, organizations including the American Heart Association, Canadian Cardiovascular Society, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Canadian Paediatric Society, and the American Academy of Pediatrics encourage all who are eligible to be vaccinated against COVID-19.

Myocarditis: COVID-19 Is a Much Bigger Risk to the Heart Than Vaccines

The heart has played a central role in COVID-19 since the beginning. Cardiovascular conditions are among the highest risk factors for hospitalization. A significant number of patients hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2 infections have signs of heart damage, and many recover from infection with lasting car

scitechdaily.com

You know what helps even more?

Natural immunity.

Infection-induced immunity and vaccine-induced immunity are pretty similar. On the whole, studies found that the efficacy of infection-induced immunity was about the same as what you’d get from a two-dose mRNA vaccine, and sometimes higher. For example, research from the U.K., in which a few hundred thousand participants were followed in a large-scale longitudinal survey, found that prior to May 16, having had two doses of the vaccine (regardless of the type) reduced the risk of testing positive by 79 percent, while being unvaccinated and having had a previous infection reduced the risk by 65 percent. After the delta variant became dominant,1 vaccination became less effective, reducing the risk by 67 percent, while a previous infection reduced the risk by 71 percent.

Likewise, both kinds of immunity seemed to wane over time — though Moore said infection-induced immunity might take longer to decline because a vaccination happens nearly all at once, while an infection takes longer to go through a process of growing, declining and finally being cleared from the body. “But it’s also not radically different [from antibody titers to vaccination]. It’s not measured in years, but months,” he said.

This is why some countries, including the member states of the European Union, treat documented recovery from COVID-19 as functionally the same as vaccination in their “vaccine passport” systems.

Still, vaccine-induced immunity is a better choice, not because it produces a stronger immunity, but because it enables you to get the immunity without the side effects and risks that come along with illness — like a greater risk of stillbirth if you’re pregnant, or long COVID, hospitalization and death in general.

How Omicron Upended What We Thought We Knew About Natural Immunity

After dizzily swelling for weeks, COVID-19 cases seem to be leveling off in New York and Chicago. In the greater Boston area, the amount of SARS-CoV-2 found in …

fivethirtyeight.com

fivethirtyeight.com

![IMG_4855[1].JPG IMG_4855[1].JPG](https://theologyonline.com/data/attachments/2/2583-89a6fe11301fbea4d10ca562a076aefb.jpg)