genuineoriginal

New member

Trying to use statistical correlation as if it is causation would lead to a lot of false conclusions.To be fair, he didn't suggest causation. I think he was trying to imply that correlation does not mean causation with drugs.

You may have posted this before reading Stripe stating the same thing.Stipe, as usual, missed the point, which is that correlation does not mean causation.

:chuckle:Edit: I see Stipe has amended his error. They were wrong about you, Stipe. You are capable of learning. Hopefully, GO will be able to figure it out, too.

Like the false conclusion that CO2 "causes" global warming?That comment was in regard to some person ignorantly supposing that such correlations actually prove something.

You would have a point if you were thinking that I was relying on statistics instead of on the stated side-effects of psychiatric drugs.Troubled students sometimes commit murder, and troubled students are often given psychoactive drugs. Likewise, troubled students often have discipline records. You could say, with equal reasonableness (or lack of reasonableness) that school discipline causes school shootings.

This is so obvious, that anyone with an open mind and normal intelligence would understand it.

Drugs That Trigger Violent Behavior

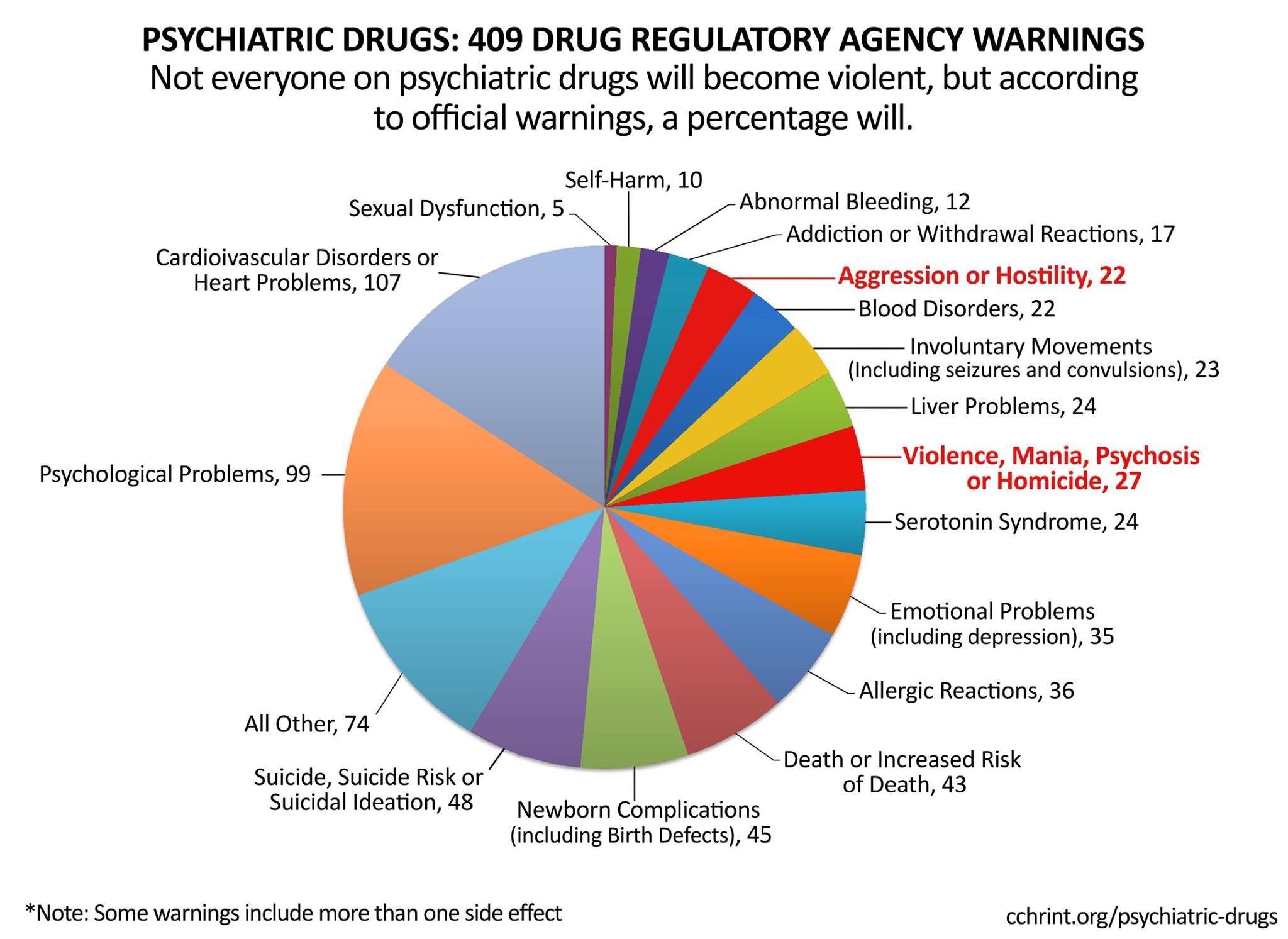

Violence as a drug side effect seems preposterous to patients, pharmacists, physicians and even juries. Trying to use the “Prozac defense” to justify killing or even hurting someone is often met with scorn.

Although drug-induced hostility or aggression has not been well studied, a surprising number of medications come with precautions about violent acts.

Antidepressant prescribing information, for example, warns physicians that, “All patients being treated with antidepressants for any indication should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual changes in behavior…” Drugs such as citalopram (Celexa), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil) and sertraline (Zoloft) carry warnings about aggressiveness, agitation, hostility, impulsivity and irritability.

Violence as a drug side effect seems preposterous to patients, pharmacists, physicians and even juries. Trying to use the “Prozac defense” to justify killing or even hurting someone is often met with scorn.

Although drug-induced hostility or aggression has not been well studied, a surprising number of medications come with precautions about violent acts.

Antidepressant prescribing information, for example, warns physicians that, “All patients being treated with antidepressants for any indication should be monitored appropriately and observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual changes in behavior…” Drugs such as citalopram (Celexa), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil) and sertraline (Zoloft) carry warnings about aggressiveness, agitation, hostility, impulsivity and irritability.

There are people studying the effect that are finding out that violence is being caused by antidepressants.

Violence Caused by Antidepressants: An Update after Munich

The Most Definite Study

Several years after the publication of the new FDA warnings, Thomas Moore and his colleagues (2010) reviewed all adverse reports sent to the FDA from 2004-2009. Their reviewed showed that the vast majority of drugs (84.7%) have two of fewer reports of violence. By contrast, a few drug classes — antidepressants, stimulants, benzodiazepines, and atypical antipsychotics — have a disproportionately larger number. The differences remain when the number of prescriptions are factored into the statistical analyses (p<0.01).

It’s not the patient’s “mental illness” that causes violence, it’s the drugs. Six of the 31 drugs associated with violence in Tom Moore’s study are not routinely prescribed for psychiatric disorders. Remarkably, by far the most dangerous drug for causing violence is Chantix (varenicline), an aid for stopping smoking. Similarly, the fifth drug is Lariam (mefloquine), an antimalarial drug, made infamous because it was taken by U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Robert Bales when he massacred Afghan noncombatants. The FDA label for Lariam states, “Mefloquine may cause psychiatric symptoms in a number of patients, ranging from anxiety, paranoia, and depression to hallucinations and psychotic behavior.” Not all psychiatric drugs are associated with violence and several non-psychiatric drugs are highly associated with violence. The data proves that the violence is associated with the class of drug and not the condition of the patient.

The Most Definite Study

Several years after the publication of the new FDA warnings, Thomas Moore and his colleagues (2010) reviewed all adverse reports sent to the FDA from 2004-2009. Their reviewed showed that the vast majority of drugs (84.7%) have two of fewer reports of violence. By contrast, a few drug classes — antidepressants, stimulants, benzodiazepines, and atypical antipsychotics — have a disproportionately larger number. The differences remain when the number of prescriptions are factored into the statistical analyses (p<0.01).

It’s not the patient’s “mental illness” that causes violence, it’s the drugs. Six of the 31 drugs associated with violence in Tom Moore’s study are not routinely prescribed for psychiatric disorders. Remarkably, by far the most dangerous drug for causing violence is Chantix (varenicline), an aid for stopping smoking. Similarly, the fifth drug is Lariam (mefloquine), an antimalarial drug, made infamous because it was taken by U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Robert Bales when he massacred Afghan noncombatants. The FDA label for Lariam states, “Mefloquine may cause psychiatric symptoms in a number of patients, ranging from anxiety, paranoia, and depression to hallucinations and psychotic behavior.” Not all psychiatric drugs are associated with violence and several non-psychiatric drugs are highly associated with violence. The data proves that the violence is associated with the class of drug and not the condition of the patient.