Fentanyl’s Wake

Communities devastated, families destroyed, and hundreds of daily dead.

The police car’s flashing lights were bright in the rear-view mirror. I was definitely over the speed limit. My older brother said something calming and sensible like, “Turn on the interior lights.”

Some of that night is hazy, some crystal clear. Because sudden death changes you. It inverts the algebra of your thinking. It changes the tenor of your voice. And it works quickly.

I turned on the light and watched the officer’s dancing white flashlight approach. Within seconds, I was making eye contact with the fifth or sixth cop I would talk to that night as the crisp cold January air flowed over my descending window in a wave.

“How we doing tonight?” the officer asked.

“Not well,” I replied.

“Oh. What’s going on?” he said back quickly, intrigued as my comment likely ran counter to the usual litany of more accommodating responses.

“Our sister died from an overdose earlier today. You guys have been at our house for the last few hours. I just picked up my brother at the airport. We’re headed back there now. Olivastro. Call it in.”

To say it so matter-of-factly haunts me still. But one’s senses are dulled quickly in the world of the opioid scourge.

“You don’t want to go in there. Trust me, I’ve done more calls like this than I want to count, and you don’t want to see her this way.”

33 years young.

“The medical examiner’s office will be here soon, they’ll move the body and check for foul play, but all the signs point to an accidental overdose.”

Clean for a year.

“We’ll do an autopsy. It takes a while for the results to come in.”

Bright and beautiful. Passionate and proud. Too much promise to be gone. Too much zest for life to believe that a body bag, with the sound of its industrial-grade zipper penetrating through two walls, could truly mean the end.

But Amy’s life did end January 18, 2016. I think about her every day.

This story is deeply personal, but—sadly enough—not solitary, and not at all unique. It all came roaring back when I read about a 13-year-old

overdosing and dying recently in Hartford, after bringing

40 bags of fentanyl into school.

As he lay dying in a hospital, police required all his classmates to walk through a solution of bleach and OxyClean—before they could

leave school—to neutralize potential exposure and ensure they weren’t transferring deadly traces outside. School remained closed for a week to cleanse the remaining remnants of the fentanyl stash found in multiple classrooms and the gymnasium.

At a community meeting, Hartford superintendent Leslie Torres-Rodriguez reportedly became emotional, calling what happened “

a surreal and devastating experience.”

Torres-Rodriguez is right. The fentanyl experience is devastating—and it’s hollowing out families and communities all across our country.

News accounts shows drug deaths have spiked everywhere. The year we lost my sister more than 65,000 people overdosed and died. That’s skyrocketed to more than 100,000 people during the 12-month period ending April 2021. That’s nearly 300 people each day.

We live in an age of data visualization, so the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers an

interactive dashboard with provisional counts of drug overdose deaths. As jarring and important as the statistics are, it’s imperative we don’t forget that each one of these is a life lost, forever. Nearly 100,000 unique individuals—with inherent value, talents, dreams, desires—vanquished by a nearly invisible foe.

It takes only 2 milligrams to be lethal. That’s not even enough to cover the year on the front of the penny in your pocket.

The scourge is so real, the only boundary that exists is in your imagination. It may be the heroin that a few years ago made its way into baby formula to

steal the breath from a 5-month-old in New Britain. Or the fentanyl that

appears to have played a role in the death of Lauren Smith-Fields, a TikTok star in Bridgeport. As

the New York Times recently reported, “In just the past few months, fentanyl and other opioids have been linked to the deaths of an 11-month-old girl in South Carolina, a 10-month-old in Pennsylvania, a 2-year-old boy in Indiana and a 15-month-old boy in California.”

The faces of death sweeping our nation include every race, color, creed, zip code—and age. The threat to the American public couldn’t be starker. Fentanyl is now the leading cause of death for Americans between the ages of 18 and 45,

according to Families Against Fentanyl. It killed more people last year than suicide, car accidents, or gun violence; and the number of fatalities has more than doubled in 30 states in just two years,

more than tripled in 15 states, and increased almost five fold in six states.

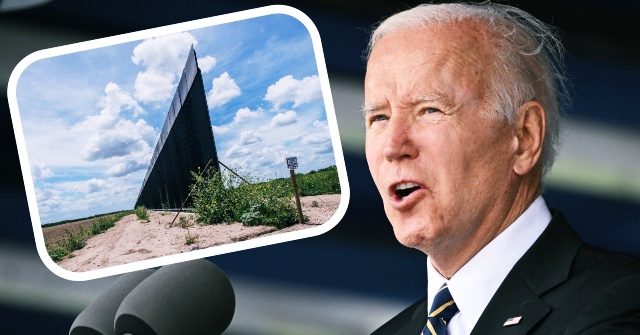

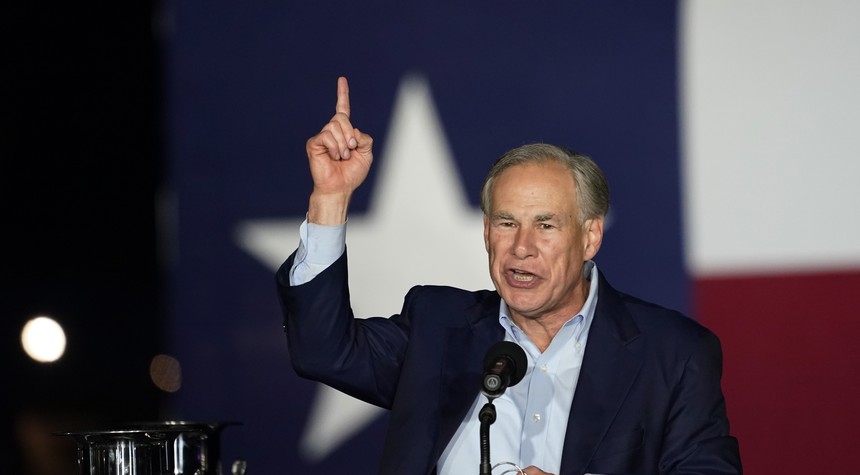

Earlier this year, Texas Governor Greg Abbott

sounded the alarm about the large amount of fentanyl coming through the southwest border, noting that his state had seized enough to kill 222 million Americans, or 67 percent of the total U.S. population. In his State of the Union address, President Joe Biden gave lip service to border security and fighting the opioid epidemic. Yet only a few weeks earlier, House Democrats

blocked a bill that would have retained stiffer penalties for those dealing and trafficking fentanyl.

Just a few weeks ago,

America lost one of its best in Bishop Evans, a 22-year-old Texas Army National Guard member who dove into the Rio Grande River to save two struggling aliens. His training and direction was specifically not to enter the water. But his instinct, his humanity, compelled him to act. As Texas officials said, “His act was heroic. His loss is tragic.”

How tragic? He died. The illegal entrants lived. They were smuggling drugs into America.

more

https://americanmind.org/salvo/fentanyls-wake/

@annabenedetti

@Rusha

Any comments?

www.americanthinker.com

www.wnd.com

www.wnd.com